A tale from the Test Valley

W. H. HUDSON WATCHED GRASSHOPPERS IN A WOOD WHERE A KING MURDERED HIS FRIEND . . .

by DENNIS SHRUBSALL

DURING the summer of 1902 while writing Hampshire Days the eminent naturalist and author W.H. Hudson spent a month in the Test Valley lodging at ‘The Sheep’s Crook and

Shears’ a riverside inn in the hamlet of Bransbury three or four miles south of Andover. This inn, once favoured by anglers, has since been converted into a private residence.

Shortly after arriving he discovered, in Harewood Forest, a colony of great green grasshoppers. It was his first experience of the species, so he returned daily to

observe them. He even took one back to his room at the inn, and so loudly did the

little creature stridulate that the locals drinking at the bar thought there was a

bird in the house. But he did not keep it captive for long before returning it to the

forest and the companionship of its own kind.

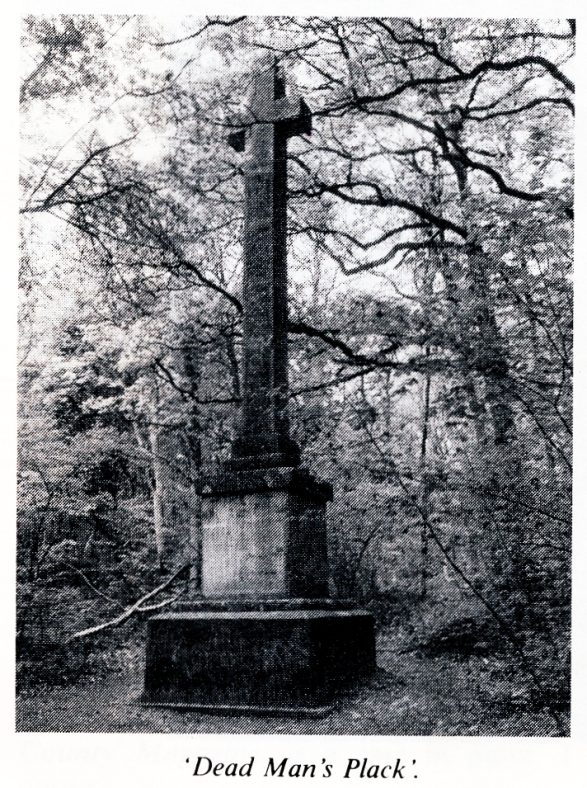

Hudson’s grasshopper colony was situated on a small open heathland, so at lunch time he would retire to the nearby trees to eat and rest in their shade. He chose a spot near a graceful eighteen foot stone cross erected seventy or so years earlier by a former owner of the land to mark the place where, according to legend, a tenth century king of Wessex, Edgar, had murdered his friend and henchman Earl Athelwold. Not, however, until reminded

of the disbelief of a professor whom he cordially disliked did Hudson decide to look into the legend for himself, and this is what he learned.

King Edgar, a widower at twenty-two, had dispatched his confidant, Earl Athelwold, to Devon to verify the reputed beauty of the Earl of Ongar’s daughter, Elfrida, whom he contemplated marrying. She was beautiful indeed, and at their first meeting Elfrida’s eyes told the already

infatuated Athelwold that she was his for she was ignorant of the king’s intention. Determined to have her, yet aware that Edgar was not lightly to be denied of or by any beautiful woman, Athelwold told him that she was merely handsome and lacked charm, later obtaining his permission to woo her himself for her inheritance. After their marriage in Devon

Athelwold took Elfrida to his secluded castle at Wherwell in Hampshire in a vain attempt to keep her from his king who, upon learning the truth, announced his intention of visiting them. The cornered Athelwold confessed his deception to Elfrida, entreating her to make herself unattractive to the king both in manner and appearance. Pretending to agree she

did precisely the opposite; and on the following day while hunting in Harewood Forest the enflamed and enraged Edgar stabbed Athelwold in the back, galloped his horse over him, and within a year wedded the willing widow. Eight years of happiness followed, culminating with Edgar’s fatal fever while travelling to Glastonbury.

Elfrida plotted to have her son, seven-year old Ethelred, succeed his father as king instead of the lawful heir, thirteen year-old Edward, child of Edgar’s first marriage. Outwitted by her implacable enemy Archbishop Dunstan who forcibly removed Edward from her custody, she

lived in comparative obscurity at Corfe Castle until, contrary to Dunstan’s instructions, she was visited by the affectionate young king whom she had murdered in much the same manner as Athelwold, and had his body buried in a thicket. However, the assassination was

witnessed by a commoner, Elfrida was denounced as a murderess, and Dunstan again removed the lawful heir — now Ethelred — from his mother’s custody and had him taught to hate and despise her. Instead of Regent of the Kingdom during her son’s minority Elfrida was now a powerless, frightened woman, hourly in fear of arrest and execution: but contrary

to her expectation Dunstan left her to answer to God alone, a prospect which, with the passing of time, filled her with even greater apprehension.

Months later when Edward’s remains were removed from their second resting place at Wareham to Shaftesbury Abbey she attempted to join the cortege, but Dunstan stopped her. She also tried to occupy her house at Sarum, but soldiers prevented her from entering the city. Lodging at nearby Amesbury she interpreted a fable related to her by her maid as God’s instruction to reconcile herself to Dunstan. Obediently she humbled herself before the clergy, established abbeys at Amesbury and Wherwell, and distributed the residue of

her wealth to the many religious houses founded by Edgar: but she did not forgive Dunstan, and when he died uttered innuendoes calculated to remind others of his misuse of spiritual things to achieve temporal authority. Finally she retired to her abbey at Wherwell, took the veil, and drowned in the stream alongside which she had often sat when newly wedded to

Athelwold.

Hudson rambled in and about Wherwell savouring the atmosphere and asking the villagers about Elfrida. Some told him that it was haunted by a female apparition: his principal informant, an old widow whose family had lived there for centuries, declared she had seen it, and Hudson hoped to hear that it was Elfrida’s ghost. But the old lady had been so terrified that she could remember only that it had a white, still face. When he left the locality Hudson

apparently lost interest in the stormy events of Elfrida’s life: Hampshire Days contains but a brief reference to the Harewood Forest cross. However, eighteen years later in Cornwall when culling some of his old papers he came across his Bransbury notes, and from them wrote a one hundred and forty page story which he called ‘Dead Man’s Plack’. It was his final excursion into the realms of pure story-telling.

This article was published in the February 1989 edition of the Hampshire Magazine

No Comments

Add a comment about this page